Our focus in the current chapter on unbearable loneliness stems from the realization that there is an extreme form of loneliness, which is felt as truly unbearable and is the type of loneliness that is not receiving sufficient attention in terms of research, practice, and prevention. We propose that it is essential that we begin to assess this form of loneliness and take preventive steps in public health campaigns to control it and limit its prevalence. It is our sense that this form of loneliness has largely flown “under the radar” due to the tendency for researchers to focus on cross-sectional research from a variable-centered perspective and not embrace a person-focused perspective.

The notion of a more extreme form of loneliness that wreaks havoc on people is not a new one. Frieda Fromm-Reichmann (1959) described this type of loneliness at length and noted that her observations were in keeping with Harry Stack Sullivan’s emphasis on an extremely unpleasant and disquieting form of loneliness that arises from unmet longings for human intimacy. Fromm-Reichmann (1959) based her description on her clinical patients. She described a psychotic loneliness that leaves people feeling emotionally paralyzed and helpless. She added that it is so severe, people are unable to talk about it and many try to conceal it. She concluded her seminal paper by noting that what she has seen clinically resembles vivid accounts of loneliness depicted by famous poets.

What are the defining features of unbearable loneliness as we see it? This is an intense form of loneliness that is marked by significant psychological pain. It is the type of loneliness referred to in suicide notes by people who say they could not bear to be alone (Coster & Lester, 2013). Unbearable loneliness is marked by psycho-logical pain and the unbearable self-consciousness that Shneidman (2001) sees at the core of the suicidal mind; unbearable loneliness tends to dominate and over-whelm people in terms of their current experiences, but it is also projected into a hopelessness and sense of unavoidability in the future.

The link between unbearable loneliness and psychological pain can be under-stood based on classic accounts of the nature of psychological pain. It is widely regarded that there are three core needs implicated in happiness and well-being— the needs for autonomy, competence, and connection. One prerequisite for the pain of loneliness is a failure to satisfy the need for connection. The notion that loneli-ness is linked with psychological pain accords with Shneidman’s views of psycho-logical pain, also known as psychache. Shneidman (1996) stated that psychache is a feeling of psychological pain that can be due to various overwhelming negative emotions (e.g., shame, guilt, angst, and fear) including loneliness. Shneidman is credited with placing importance on psychological pain as the key component in susceptibility to suicide. Shneidman (1993) concluded that psychological pain is experienced when important psychological needs are frus-trated to the point of feeling and seeming unendurable. Shneidman was a proponent of the psychological needs theory of his mentor Henry Murray (see Murray, 1938). Shneidman identified several psychosocial themes, including the need to affiliate and the need to be loved. Unbearable loneliness tinged with psychological pain should result when these types of needs are unsatisfied, and the prospects for addressing these needs seem bleak. Specifically, through this lens of unmet needs, loneliness should seem particularly unbearable when it is accompanied by feelings of helplessness and hopelessness, and with no clear steps or pathways to addressing feeling so overwhelmingly alone.

Aloneness Intolerance

Eccles and Qualter (2020) have noted that learning to tolerate feelings of loneliness is considered an adaptive, natural, and necessary component of human life. Some people do manage to cope with loneliness through acceptance and reflection and other strategies (Rokach, 2018). What is crucial to consider is that there are indi-vidual differences in the ability to adapt to being alone and experience feelings of loneliness, and unfortunately, many people seem to lack this tolerance capacity.

Windy Dryden (1999) has described a form of aloneness intolerance that seems to be clearly implicated in a vulnerability to unbearable loneliness. As described by Dryden (1999), there is an irrational aspect to this intolerance that seems to be rooted in our beliefs that a person must have the company of others and should have an emotional connection to these others. In keeping with our discussion of negative self-views, Dryden suggested further that this intolerance is fueled by ego-related concerns that result in a person concluding that loneliness means being less worthy. This intolerance can apply to being physically alone or emotionally alone, but most importantly, it is both seen as intolerable and it feels painfully intolerable.

This inability to tolerate being alone and loneliness is frequently mentioned by guests appearing on the longstanding BBC radio show Desert Island Discs. Most guests are asked if they could actually stand it if the show’s premise came true (i.e., being castaways by themselves on a desert island). The responses have varied con-siderably with some people indicating that it would be no problem and some indi-cating they couldn’t bear it for very long, if at all. This aloneness intolerance has been documented in case examples. For instance, Blatt (1974) recounted the case of Mrs. H., whose clinical condition was marked by a great difficulty in tolerating feel-ings of distress. She had extensive depressive features and related concerns that could be traced to feelings and thoughts of being unwanted, unloved, and aban-doned. Another case, this one taken from an emotion-focused therapy perspective recounted by Dillon et al. (2018), also identified loneliness as the core emotion for a client suffering from depression and how her loneliness was linked complexly with shame and fears of abandonment. Despite what seems to be compelling clinical and anecdotal accounts, the lack of an extensive focus on unbearable loneliness in the broad empirical literature is somewhat ironic given the number of scientific authors who routinely refer to “the pain of loneliness.” Even a brief and cursory survey of the published literature yields countless references to loneliness as a form of pain and which accords with clinical case accounts which describe how for some people, loneliness can be severe and persistent and simply unbearable (also see Hyatt, 2010; Stein et al., 1989).

As a source for identifying an important phenomenon, case analyses of people suffering from extreme forms of loneliness such as the one of Mrs. H. cited above are highly instructive and illustrative in terms of providing a clear sense that unbear-able loneliness exists and is devastating at the individual level. Case accounts repre-sent useful reminders of the need to take a person-focused perspective and not simply focus on variables. Indeed, in addition to the published case accounts described above, we would be remiss if we did not mention celebrities and public figures who clearly have suffered from unbearable and painful loneliness. Such accounts of people in prominent view provide compelling stories for discourse about public health matters. They also remind us that fame is not a panacea for loneliness and may in fact contribute to loneliness. Judy Garland is arguably the most well-known example. It is evident in reading accounts of this iconic singer- actor’s life story that loneliness and insecurity fuelled her problems with depression and addiction and associated relationship problems. Indeed, Judy Garland once stated that “If I am a legend, then why I am so lonely?”. Garland’s unbearable lone-liness was so painfully evident and so prominent that it resulted in a New York Times article in 1969 at the time of her tragic death at age 47 with the headline “Judy Garland: Loneliness and Loss” (see Canby, 1969).

The acclaimed author Sylvia Plath described a loneliness tinged by psychologi-cal pain when she wrote in her journal, “Yes, there is joy, fulfillment and compan-ionship – but the loneliness of the soul in its appalling self-consciousness, is horrible and overpowering” (Plath, 2000, p. 31). Vincent Van Gogh is another famous indi-vidual, an innovative artist whose persona paints a poignant example of unbearable loneliness. He shared his private suffering from overwhelming loneliness in his per-sonal letters to his brother Theo (see Stone, 1969). For instance, in a letter dated September 1883, the genius artist who depicted with swirling brushstrokes the uncertainty and solitude of a starry night referred to “the peculiar torture of loneli-ness” (p. 260) and the loneliness he had to bear now that he was regarded by every-one as “… a lunatic, a murderer, a tramp.” Autobiographical accounts such as Van Gogh’s offer a window into the soul of the exceptionally lonely person who is also a well-known public figure. Poignant references to unbearable loneliness are also on display in the publicly available diary accounts of Canadian Prime Minister Mackenzie King. King is Canada’s lon-gest serving Prime Minister. King retired from politics in late 1948, and it was not long after that he died in July 1950. King never married and had incurred the loss of most of his family members as well as his beloved dogs. King may be someone who represents an individual example of how loneliness contributes to mortality. Regarding loneliness, his diary accounts found on the Government of Canada site include such statements as “I continue to feel desperately lonely,” “I felt rather help-less when I got back … and feeling so completely alone”. This refers to when he lived by himself at his Kingsmere Estate. He summarized this phase of his life by writing “It is inexpressibly lonely here, all alone.” It should be noted that King expressed his wishes that his diaries never be made public, so his diary accounts can be regarded as representing an unvarnished look at his internal world.

A related question that struck us while considering these case examples of peo-ple suffering from unbearable loneliness was “To what extent do existing loneliness measures assess unbearable loneliness?” Our analysis of the original 20-item UCLA Loneliness Scale (Russell et al., 1978) identified several items that seemingly tap unbearable loneliness. Perhaps this reflects the origins of these items. The 20 items in the original loneliness scale were first included in a dissertation by Sisenwein (1964) who compiled a list of 75 items. These items came from published descrip-tions of loneliness and the descriptions of loneliness provided by a group of psy-chologists who were surveyed. The items reflect a blend of feeling abjectly alone, having no one to provide contact and comfort, and not being about to tolerate the loneliness. Russell (1982) noted that mean scores on the original UCLA Loneliness Scale were considerably higher among people presenting at a clinic due to problems with loneliness when their scores were compared to the scores for a nonclinical sample, a pattern which recognizes the clinical significance of loneliness.

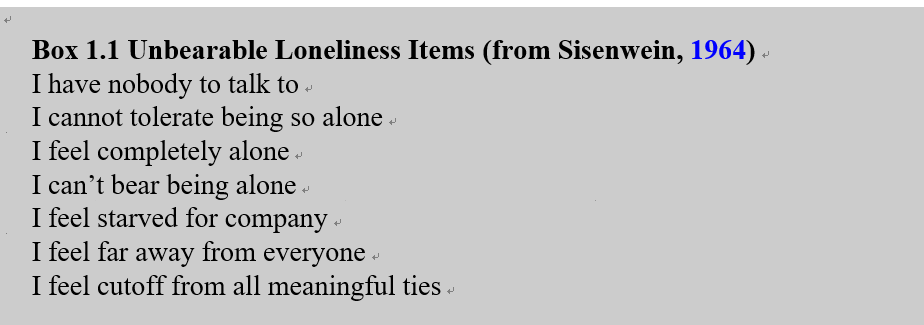

The seven items we deemed as having high content and face validity in terms of representing unbearable loneliness are listed in Box 1.1. Note that we selected items that did not have explicit references to item content specifically related to depres-sion, sadness, or lack of happiness. However, we did select items that tap an “all-ness” or “completeness” in terms of being away from everyone and feeling cutoff from all meaningful ties. Collectively, these items tap into a sense that loneliness is intolerable and entails feeling extremely and entirely isolated from people with the prospect of not feeling lonely seeming remote and unlikely to achieved. Russell (1982) detailed how a revised UCLA Loneliness Scale was developed because the original 1978 version consisted entirely of items worded in the loneli-ness direction (e.g., I cannot tolerate being so alone). Unfortunately, the creation of a more balanced version with items worded in the non-lonely direction resulted in dropping several items tapping more extreme aspects of the construct. Thus, in more contemporary versions of the UCLA Loneliness Scale, the items that remain do not assess unbearable loneliness. Further, among other extant loneliness questionnaires, in most instances, key facets of the loneliness construct with considerable clinical relevance are not being measured (for an analysis, see Maes et al., 2022).

The proliferation of loneliness measures that fail to assess unbearable and endur-ing loneliness has some key implications. For instance, it has been concluded on the basis of a review and meta-analysis that psychological interventions addressing loneliness are effective, with about 90% of the studies being based on the evaluation of cognitive-behavior therapy (see Hickin et al., 2021). But it is unknown at present whether treatment is effective for unbearable loneliness because this form of loneli-ness is simply not assessed by the outcome measures used thus far in intervention research. In general, it is typically the case that more extreme levels of distress and dysfunction pose unique treatment challenges; when people have forms of distress that are extreme, enduring, and unbearable, successful treatment often means reduc-ing but not alleviating distress as people continue to experience residual symptoms that still leave them vulnerable.

Clearly, an important question moving forward is, “To what extent do psycho-logical treatments ameliorate unbearable and enduring loneliness?” It is unlikely that brief interventions of limited scope will address the needs and vulnerabilities of people with extreme loneliness, especially if they also having limited conditions that add to their sense of isolation.