THE YUCATÁN’S GILDED AGE

The late 19th century was a boom time for the Yucatán, with a prosperity based on ‘green gold,’ henequen from the agave plant, used to make the rope known as sisal. Such was the demand from Europe’s and the United States’ farms, ships, and factories for sisal rope that the Yucatán became the wealthiest state in Mexico, and by around 1900, Mérida could boast more millionaires per capita than any other city in the world. Railroads were built for exporting the rope, and politicians hailed the sisal boom as the triumph of progress. A broad new avenue was created, Paseo Montejo, flanked by mansions in ornate European styles. Henequen plantation owners lived like kings, their children educated at the best schools in Europe, their wives dressed in the latest Parisian finery – all attained, however, at the expense of their Maya laborers, who were practically slaves. Henequen was exported and the French bricks and tiles that came back as ballast were used to build mansions for the tycoons in Mérida.

At the same time, the Maya peasants employed on henequen plantations were cruelly abused with near-slave status, and often paid in tokens that could be exchanged only in stores owned by the landowners. The situation in rural Mexico, under the regime of dictator Porfirio Díaz, was exposed by American journalist John Kenneth Turner in his 1910 book Barbarous Mexico. This led even the London Daily Mail to protest: ‘If Mexico is half as bad as she is painted by Mr Turner, she is covered with the leprosy of a slavery worse than that of San Thome or Peru, and should be regarded as unclean by all the free peoples of the world.’

Today, many of the plantation haciendas lie abandoned and crumbling, but some are open to visitors, such as the one at Yaxcopoil (www.yaxcopoil.com), which offers tours, a restaurant, and accommodations. A giant Moorish-style double arch on the highway leads to the main house, a series of large, airy rooms full of period furniture; next to the private chapel with its shiny marble floor, an ancient kitchen opens onto a garden of citrus trees and banana plants. Other haciendas, such as Temozón (ihg.com) between Mérida and Uxmal, or San José Cholul toward Izamal, have now been turned into the Yucatán’s most distinctive luxury hotels.

Quote

‘If the number, grandeur, and beauty of its buildings were to count towards the attainment of renown and reputation in the same way as gold, silver, and riches have done for other parts of the Indies, Yucatán would have become as famous as Peru and New Spain have become.’

Fr. Diego de Landa

Uxmal

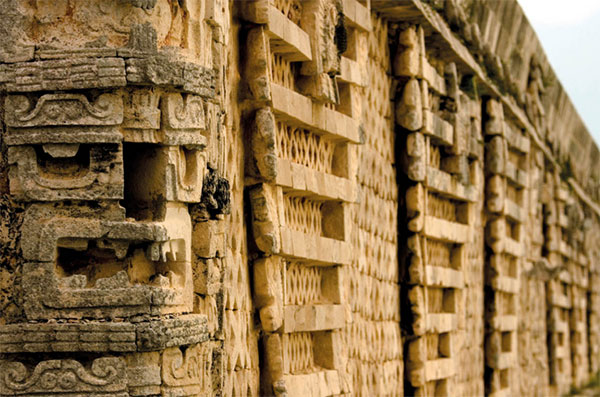

About 80km (50 miles) south of Mérida you come to Uxmal 2 [map] (daily 8am–5pm), one of the most impressive ruins in the Maya world and a Unesco World Heritage Site. Uxmal was the most important Puuc center, reaching its peak between 800 and 1000, and its architecture is stunning. In 1840, the US explorer John Lloyd Stephens compared the Palacio del Gobernador (Governor’s Palace) favorably with Grecian, Roman, and Egyptian art. ‘The designs are strange and incomprehensible, very elaborate, sometimes grotesque, but often simple, tasteful, beautiful,’ he wrote. The palace, 100 meters (330ft) wide with an impressive facade, sits atop a hill. In the Puuc style of building, rubble-filled walls were faced with cement and the whole edifice was covered with limestone mosaic panels, 20,000 of them in this case.

The Nunnery Quadrangle at Uxmal.

Alex Havret/Apa Publications

To the north of the palace is the 39-meter (128ft) high Pyramid of the Magician, legendarily built in one night by an alux, a spirit that was the son of a witch, but actually the product of several generations of builders (Uxmal means ‘three times built’). Immediately west is the 74-room quadrangle referred to as the Cuadrángulo de las Monjas (Nunnery Quadrangle), because its form reminded the Spanish priest Father Diego López de Cogolludo, who named Uxmal’s main buildings, of a convent. Though made up of four separate buildings, it forms an elegant ensemble; the entire complex is built on an elevated man-made platform and typifies the Puuc architectural style, which is based on the Maya hut, the na, with its wooden walls and high-peaked thatch roof. To the south of the Nunnery is a ball court, beyond which, sharing the Governor’s Palace platform, is Casa de las Tortugas (House of the Turtles), which gets its name from the turtle carvings on the cornice, an animal associated with rain in Maya legend.

West of the pyramid is El Palomar (House of the Pigeons), while southeast of the Governor’s Palace, is the pyramid called the Casa de la Vieja (House of the Old Woman), which Maya legend avers was the house of the sorcerer-mother of the dwarf magician who built Uxmal.

The Visitors’ Center at the entrance includes a shop, museum, and restaurant. The 45-minute sound and light show is at 8pm (Nov–Mar 7pm); an English translation is provided through headphones. Regular buses connect the site with Mérida, and a daily tour bus also leaves Mérida’s second-class bus station at 8.30am for Uxmal and the other main Puuc sites.

Chichén Itzá

Just off Highway 180 about 116km (72 miles) east of Mérida is Chichén Itzá 3 [map] (named from the Yucatec Maya chi = mouths; chen = wells; Itza = the people believed to have settled here), the best known of all Maya sites. It is a Unesco World Heritage Site and was also voted one of the ‘New Seven Wonders of the World’ from a selection of 200 monuments in 2007.

Curiously, Chichén Itzá is a very atypical Maya site. Its largest buildings – the Pyramid of Kukulcán, the Temple of the Warriors – are very ‘un-Maya’ in style, and much more similar to buildings in central Mexico. It used to be thought that Chichén Itzá had initially been a purely Maya city, which around the year 1000 was taken over by warlike invaders from central Mexico called the Toltecs, who were later replaced by another non-Maya people, the Itzaes. However, as more and more of the blanks in Maya history have been partially filled in, this theory has been largely discredited, as the successive invasions do not seem to match with any established dates. Instead, Chichén Itzá seems from its beginnings to have been a mixed community, combining Maya traditions with those of migrants from central Mexico. It grew up late in the Classic Maya era, around 700, but from around 800 dominated the north-central Yucatán for several centuries. The city declined more slowly than other Maya centers, and only finally disintegrated as a political entity around 1200.