The Nicaragua Revolution

With the backing of the US, the Somoza family political dynasty came to power in Nicaragua in 1912 and would rule for the next seven decades. With wealth from US-based multinational corporations and the backing of the US military, their rule was characterized by rising inequality and widespread political corruption.

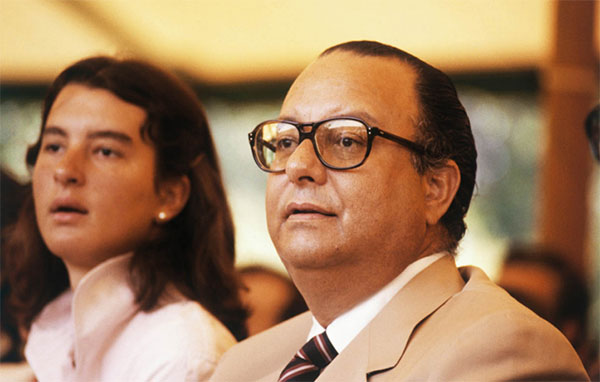

General Anastasio Somoza, the President of Nicaragua, 1975.

The Sandinista National Liberation Front (FSLN) arose in response to the Somoza family. In 1961, Carlos Fonseca Amador, Silvio Mayorga, and Tomás Borge Martínez formed the rebel group along with students, peasants, and other anti-Somoza elements, such as the Communist Cuban government, the Panamanian government of Omar Torrijos, and the Venezuelan government of Carlos Andrés Pérez. By the 1970s they were strong enough to begin plotting against the regime of long-time dictator Anastasio Somoza Debayle. They began a campaign of kidnappings, which earned them national recognition as the opposition force. The Somoza’s regime retaliated hard, using their US-trained military and police forces to torture, intimidate, and censor the Nicaraguan public. A destructive 1972 earthquake added to the unease.

In 1978 the administration of Jimmy Carter cut off aid to the Somozas because of human rights violations. Riots broke out in Managua after the editor of the leftist Managua newspaper La Prensa was murdered, and a general strike followed in Nicaragua’s large cities calling for the end of the Somoza regime. The violence continued to worsen. In 1978, the FSLN took around 2,000 people hostage at the National Palace in Managua and the government agreed to pay $500,000 and release certain prisoners. A year later, negotiations took place, managed by the Organization of American States, but they broke down. Within months, the FSLN took over the country and President Somoza resigned.

When the Sandinistas took over, the country was in ruins. Of the total population of 2.8 million, around 600,000 Nicaraguans were homeless and 150,000 had become refugees or were in exile. All wealth was concentrated in Managua, while the rest of the country had little. The revolution brought about a restructuring of all sectors of the economy. Agrarian reforms gave away much of the land to farmers. Ceremonies were held around the country where President Daniel Ortega gave peasants titles to land and a rifle with which to defend it.

While the Carter administration tried to work with the FSLN, the subsequent Ronald Reagan administration was bent on a strict anti-Communist strategy that would isolate the Sandinista regime. An anti-Sandinista movement was begun by former members of the Somoza regime’s National Guard unit along the border with Nicaragua, which was known as the Contrarrevolución (Counter-revolution), aka Contras. Other minority groups along the Mosquito Coast also began demanding more autonomy. Reagan cancelled economic aid to Nicaragua and covertly began supporting anti-Sandinista forces.

Ríos Montt was ousted in 1982 by his defense minister, Mejía Víctores, who observed that “Guatemala doesn’t need more prayers, it needs more executions.”

Central America was already destabilized by ongoing civil wars in El Salvador and Guatemala, so Nicaragua was a powder keg waiting to explode. The CIA-backed Contras secretly opened a ‘second front’ on Nicaragua’s Atlantic coast and Costa Rican border. So instead of reform and development, more than 50 percent of the FSLN’s budget was dedicated to the military. By 1982, Contra forces launched a series of assassinations of government officials and the following year began planting mines in Nicaragua’s harbors to stop shipments of weapons from reaching Managua. The US Congress enacted legislation to suspend further aid to the Contras later that year, although Reagan attempted to illegally supply them out of the proceeds of arms sales to Iran, an act known as the Iran-Contra Affair. With the help of mediation by other Central American nations, the Sapoa ceasefire between the Sandinistas and the Contras was signed on 23 March, 1988, which called for a democratic election to be held in 1990. The FSLN lost the election to the National Opposition Union, though they still controlled the army and courts. For the next seven years, Violeta Chamorro’s presidency would be dedicated to consolidating democratic institutions and stabilizing the economy.

Salvadoran Civil War

At the start of the 20th century, the Salvadoran economy revolved around coffee, sugar cane, and cotton, which were controlled by just a few families. Rural resistance began to bubble up, most notably in 1932 when peasants around the country began to protest. The government retaliated in what has become known as La Matanza, or the slaughter. Roughly 40,000 Indigenous farmers and political opponents were murdered, imprisoned or exiled during the act.

House after a Salvadoran army and guerrilla battle, 1983.

From the 1930s to the 1970s there was widespread instability and El Salvador’s authoritarian governments quashed any form of rebellion. Attempts at democratic reform were extinguished and government opposition turned to armed resistance. In 1979 the reformist Revolutionary Government Junta took power, angering both the left and the right. Civil war broke out. The army became involved in indiscriminate killings, most notoriously the El Mozote massacre in December 1981, when 800 civilians were brutally murdered.

As the US backed the government and Cuba and other communist states supported the growing insurgency, a proxy war ensued. The Chapultepec Peace Accords marked the end of the war in 1992, and the Farabundo Martí National Liberation Front (FMLN), initially formed from guerilla groups, became one of the major political parties. Many military functions were transferred to civilian control and the size of the armed forces were dramatically reduced; it has since become one of the most respected institutions in the country. Many guerrillas and soldiers who fought in the war received land under the peace accord-mandated land transfer program, which ended in January 1997.

Costa Rica’s War of National Liberation

Costa Rica’s War of National Liberation began on March 11, 1948. It consisted of a well-planned offensive carried out by men with no formal military background, trained by guerrilla fighters from the Dominican Republic and Honduras, and armed with guns flown in from Guatemala. Forty-four days later, 2,000 men, one in every 300 Costa Ricans, had been killed during the violent, sad war of liberation. José Figueres’ forces were victorious, despite the efforts of the former Nicaraguan dictator Anastasio Somoza García, and his invasion of the north of Costa Rica. President Teodoro Picado, who had never really believed an armed insurrection would occur, and who had no heart for conflict, saw that a swiftly negotiated peace was essential; he announced his surrender.

Costa Rican government troops, 1948.