THE MARIMBA

Developed by African slaves in Central America, the marimba has become the most important folk instrument in the region since being introduced in the 16th or 17th century. The instrument was descended from an ancestral balafon, which consisted of a set of wooden bars, arranged like keys on a piano, struck with mallets. The marimba is like a xylophone, but with a more resonant and lower-pitched tessitura. During the 18th and 19th centuries the instrument became more prevalent, and its sound is now widespread in musical genres throughout the region, from woodwind and brass ensembles to marching bands and contemporary orchestras.

In Panama, salsa musician Rubén Blades has achieved international stardom and is a national icon.

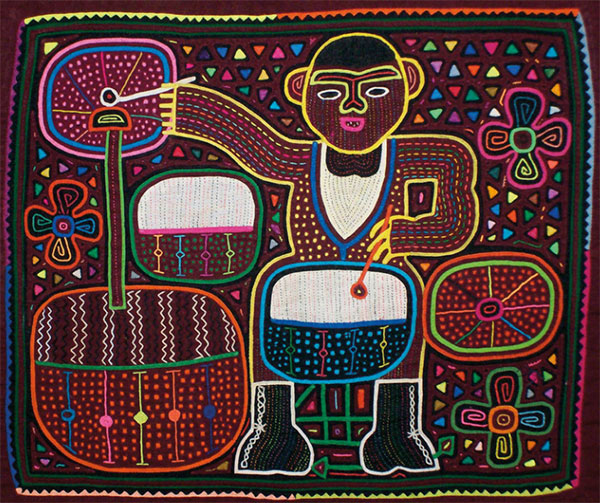

A jazz drummer applique design by a Kuna Indian artist, Panama.

Latin jazz

Central America has a strong jazz legacy, particularly Panama. The country has a long history in the musical genre. In the 1940s, the port city of Colón boasted at least ten local jazz orchestras, with local legends that included pianist and composer Victor Boa, bassist Clarence Martin, singer Barbara Wilson, and French horn player John ‘Rubberlegs’ McKindo. This jazz legacy was recently reinvigorated when the US-based Panamanian pianist Danilo Perez organized the first jazz Festival in January 2004, then opened a jazz club in 2015 inside the American Trade Hotel in Casco Viejo. Minor jazz scenes can be found in large metropolitan areas throughout the region, such as San José and Guatemala City.

Afro-Caribbean music

Along Central America’s Caribbean coast the music is influenced by Jamaica and other West Indian islands that have had a long history of migration. Originating in Trinidad and Tobago in the early to mid-20th century, calypso found its way to Costa Rica and Panama, particularly the stretch of coast from Puerto Limón to Bocas del Toro. In Cahuita, Panama-born musician Walter Ferguson had some minor success in the 1970s and 1980s, but his fame was resurrected in 2002 with the release of the album Dr. Bombodee, from Costa Rican label Papaya Music.

Reggae en Español, or Spanish reggae, originated in Panama, and is similar to Jamaican dancehall music. Some songs are simply Jamaican songs translated into Spanish, something often criticized as plagiarism, though many original reggae artists can be found from Belize to Bocas del Toro. Spanish reggae is a predecessor in the region to reggaetón, a mix of hip hop, bachata, salsa, and electronic music born in Puerto Rico in the 1990s. Central American reggateón artists have found considerable success on the larger Latin American scene, such as Panamanian rapper Lorna’s 2003 hit Papi Chulo (Te Traigo el Mmm).

Punta, a style developed by the Garífuna, is a contemporary adaptation of traditional Garífuna songs and dance. In its original form, punta consisted of a man and woman competing against each other by shaking their hips and moving their feet to the beat of a drum, though the sexual undertones have now been toned down somewhat. Modern punta mixes Garífuna rhythms with a little bit of reggae, R&B, and rock.

The Congo dance, passed on from generation to generation, tells a story of characters in a fight with the devil, who is loose during Carnival.

In Colón and Portobleo on Panama’s Caribbean coast, Congo is a form of music and dance with colorful costumes that originated with escaped slaves that lived in the rainforest, known as Cimarrones. Performed mostly during festival times, Congo is distinguished by the use of upright drums and wild, lascivious movements and lyrics. The primary performances take place on the Tuesday and Wednesday before Lent, allowing practitioners to celebrate and share their oral history and traditions.

Visual arts

In Central America, the visual arts have mostly been a response to indigenous traditions and Western European movements. The rich history of art in the Maya region predates the arrival of Europeans, with murals and carved stone stelae by the Mayans. During the colonial period, the church not only exerted enormous power over the lives of the European and indigenous peoples, but also the nature of the visual arts. Indigenous traditions merged with the Christian teachings of Franciscan, Augustinian and Dominican teachings, resulting in unique mestizo works from mostly anonymous artists.

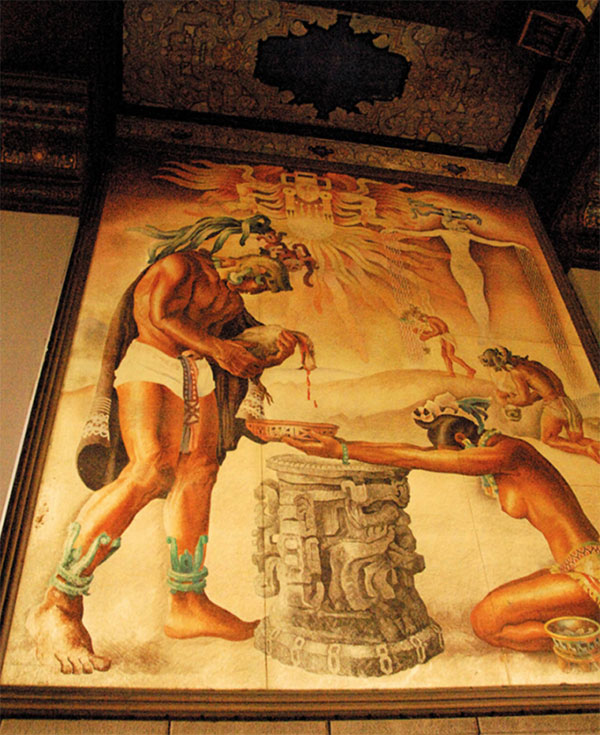

In the late 1920s in Escazú southwest of San José, a group of artists developed the ‘Landscape’ movement in Costa Rica. Calling themselves the Group of New Sensibility, they portrayed rural Costa Rica in bright vibrant colors. Throughout the 20th century, however, rather than portray natural settings, most art produced in the region has embodied critiques of social, political, and economic conditions, often in the hopes of bringing international awareness to the poor conditions in which many live. For example, the Indigenismo movement advocated for a dominant social and political role for indigenous peoples in countries where they constitute a majority, such as Mexico and Guatemala. This often-romanticized view of native culture can be found in the murals and paintings of Alfredo Gálvez Suárez (1899–1946) and Carlos Mérida (1891–1984).

Alfredo Galvez Suarez’s Mayan mural, Guatemala.

Alamy

Originating in the 1970s on the islands of Solentiname in Lake Nicaragua, the Primitivista painting movement was influenced by the Haitian painting renaissance of the late 1940’s and 50’s, and idealized scenes of everyday life in natural environments in bright colors and intricate detail. The idea embodied hope and possibility, something at odds with the Somoza regime, which eventually bombed the artist community on the islands and forced the remaining artists into hiding. After the Sandinista revolution, the painting workshops reemerged; subsequently, many members of the group have won national prizes and exhibited in North America, Europe, and Japan.