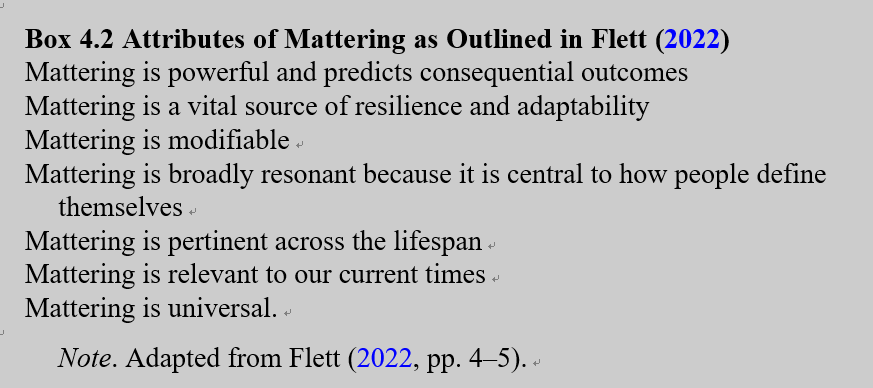

By now, it should be the case that most readers will be eager for a reminder that mattering is double edged and mattering is an exceptional positive resource. While much of the focus in this chapter has been on feelings of not mattering and how they relate to the will to die, positive feelings of mattering can be fundamental to the will to live. I noted in a recent review that mattering is “an essential way of life” (Flett, 2022, p. 3). The healing and protective power of mattering is reflected in the conclu-sions that were reached about mattering are listed in Box 4.2. Given these attributes, we need to proactively put mattering to work to protect people and improve their lives.

I will preface the final segment of the chapter by proposing that the best way to recognize the potential, power, and potency of mattering in terms of its role in key applications is to place mattering right at the center of initiatives. An explicit focus on mattering is very much in keeping with the realization that for many people, their feelings of not mattering and their core need to matter is the most salient psycho-logical theme in terms of their sense of self and identity, and it is indeed central to how they define themselves. Accordingly, I discuss below the approaches I have labeled “mattering-centered prevention” and “mattering-centered care.” This spe-cific emphasis on mattering implies that making mattering the focal point can ben-efit anyone in terms of resilience and recovery. Some specific observations about the utility of a mattering-centered approach to prevention and treatment are presented below. This segment of the chapter briefly touches on these issues. A considerably more extensive discussion can be found in Flett (2018b). A key point to reiterate is that when it comes to prevention and intervention, mattering should not be equated with belongingness. There are many things that can be done to enhance someone’s sense of being important to others, and this involves making them feel heard, seen, understood, and accepted. Belongingness is not as easy to implement and relative to mattering, it may be rooted in broader social and societal influence.

One of the most remarkable things about the mattering construct is that not only is it implicated in vulnerability to suicide, it is also highly relevant to prevention and intervention. The prevention role has already been emphasized above with focus on the “You Matter” slogan and related campaigns.

Although he did not mention the need to matter, Shneidman (1996) was quite clear about how the treatment approach for someone who is suicidal must have a primary focus on the unmet psychological need or psychological needs that are central to their experience of psychological pain. If the core vulnerability and source of pain for someone is their failure to matter to other people or to society as a whole, then this need must be the main target. It is vital to for therapists and counselors to gain an understanding of what has contributed to feelings of not mattering, includ-ing whether a previous sense of being significant to others has been lost and why it has been lost.

Regarding its role in prevention, Flett (2018a) has discussed at length how a focus on mattering promotion should be at the center of any initiative designed to build mentally healthy schools. It was noted previously that, “… a key element of interpersonal resilience and a foundational aspect of the mentally healthy school is the feeling of being important, valued, and seen positively by other people …” (p. 383). But prevention also needs to consider older people. Indeed, we have incor-porated an emphasis on mattering into a research program dedicated to safeguard-ing potentially vulnerable men making the transition to retirement (see Flett & Heisel, 2021; Heisel et al., 2018, 2020). Because mattering is the community is a feeling that is linked with better mental health (see Flett, 2018b), there is much that communities can do to let its members know they are valued. What is needed is an approach patterned after the proactive initiatives taken by organizations such the Maine Resilience Building Network. This organization has the goal of improving feelings of mattering among every child and adolescent in Maine. This approach recognizes that even small acts and gestures can make a difference. Communities can go even further and adopt the same approach and apply it to people of all ages.

Why should the emphasis be on mattering-centered prevention? There must be an explicit focus on the promotion of mattering because more general programs will not address the specific vulnerability that was described earlier. For instance, when it comes to school-based initiatives, Flett (2018a) noted that programs that focus on themes such as mindfulness and self-regulation can be beneficial, but only to a lim-ited extent when the main vulnerability for a unique person is the feeling of not mattering to other people and not mattering at school. A key element of the “You Matter” focus is that it important to send that message to those who are in a position to intervene and boost a vulnerable person’s sense of mattering. There is a role for people of all ages, but especially young people, in terms of finding ways to make other people feel like they matter. Thoughtful ges-tures and timely encouragement can make the difference. This key point cannot be overstated. It also needs to be recognized that when it comes to prevention efforts aimed at young people, there needs to be components that are youth-led in keeping with the notion that mattering involves a feeling of being seen, heard, and taken seriously, especially about matters that pertain to young people.

As noted above, although he did not refer specifically to mattering, Shneidman (1984) reached a similar conclusion based on his analysis of the gifted young people in the famous Terman study who did or who did not take their own lives. Shneidman (1984) observed that in some instance, significant others play a vital role. He men-tioned this within the context of a vulnerable man who had been in the Terman study who definitely would have attempted suicide if not for the intervention of his loving wife. The other element that this example underscores is that many people have feelings of mattering or not mattering that are veridical because they have been sent clear and unequivocal messages from the people in their lives.

The role of mattering in clinical assessment and intervention is also very impor-tant. I have discussed this at length in a clinically focused chapter in my book on the psychology of mattering (see Flett, 2018b). Given the brevity and apparent reliabil-ity and validity of measures such as the General Mattering Scale and the Anti- Mattering Scale, their inclusion in assessment batteries seems warranted. These measures can be used in initial assessments, but these measures are also sensitive to change and can be used to determine whether there has been meaningful improve-ment. Mattering can also be injected as a focus in clinical interviews. Probes that ask people to name who makes them feel like they matter can be exceptionally revealing in terms of getting people to talk about themselves and their lives.

A complete analysis of the role of mattering in treatment and recovery is beyond the scope of this chapter. However, in previous work (see Flett, 2018b), it was noted that mattering is highly relevant to the therapeutic relationship between the client and the therapist. If an approach is truly to become mattering-centered care, then it is essential to put in place conditions that will build a sense of mattering. This will include making the vulnerable person in pain feel truly listened to and understood at a level that may be a rare experience for this person. It will also include making it clear that there is an atmosphere of acceptance without conditions such that there will be no undermining or negating of emotional experiences; the message needs to be sent that if a person truly matters, her or his emotions also matter. The overarching goal of any mattering-centered care is how it feels to be cared about. When someone realizes that someone cares about them, they can no longer hold on to the view that no one cares about them; this alone should lessen unbear-able feelings of pain and unbearable feelings of not mattering to others. The realiza-tion that someone truly cares and values them will mean that overgeneralized views of the self (i.e., I matter to no one) no longer apply and this should be one very significant step that places the vulnerable person on the road to recovery.