FLYING THE FLAG

Central America’s strategic location between the Atlantic and the Pacific was emblematic for the formation of the short-lived Federal Republic of Central America. The federation’s flag displayed a white band between two blue stripes, epitomizing the land between two oceans, while the coat of arms showed five mountains, each signifying a different state, between two oceans. Even after the federation fell apart, the idea remained symbolic. Even today, Guatemala, El Salvador, Honduras, Nicaragua, and Costa Rica still fly flags that retain the old federal motif of two outer blue bands bounding an inner white stripe.

Morazán wore out his welcome when he attempted to use Costa Rica as a base to revive his moribund confederation. The general sent missives to the other Central American countries calling for a National Constituent Assembly to revive his dream of a unified Central American nation. He threatened to impose compliance by force of arms. When Morazán tried to conscript Costa Ricans to enforce his ultimatum, the people of San José revolted. After three days of fierce fighting, Morazán was captured and, on September 15, 1842, he was executed in San José’s Central Park. Less than three years later, Braulio Carrillo, too, was to meet a violent end, assassinated in El Salvador.

William Walker

A decade after Morazán’s attempt at unification, El Salvador, Honduras, and Nicaragua created the Federation of Central America, but it too fell apart. In the 1880s, Guatemalan President Justo Rufino Barrios tried to take over the region by force and was killed in the process. Other attempts were made in 1896 and 1921 and didn’t last more than a year or two. While the different nations of Central America were never able to unite politically, they were able to form a military coalition in 1856–7 to fight off an invasion by US adventurer William Walker.

In 1855, the Tennessee-born Walker took control of Nicaragua after conducting a farcical election. One of his aims was to institutionalize slavery there and in neighboring countries so that he could sell slaves to the United States. Certain US industrialists liked the plan and gave support to Walker. The following year, with an army of 300 mercenaries, called filibusteros, he invaded Costa Rica, advancing as far as the site of the present Santa Rosa National Park. Walker and his men entrenched themselves in the fortified Santa Rosa mansion. Costa Rican President Juan Rafael Mora, a member of the coffee oligarchy, had been monitoring the threat and had already mustered a force of campesinos (farm workers) to repel Walker. The Costa Ricans were numerically superior, though many were poorly armed with little more than farming implements and rusty rifles. On May 20, 1856, they engaged Walker in a 14-minute-long battle and forced him to retreat toward the Nicaraguan border.

The Costa Rican army pursued them and, at Rivas in Nicaragua, trapped Walker in a wooden fort. A young drummer boy named Juan Santamaría volunteered to torch the fort, but was shot dead in the process. With the fort in flames, Walker’s men were routed. Three years later, he met his end in front of a firing squad in Honduras.

Two waves of immigration changed Belize considerably: 2,000 people from the Mosquito Coast, a British settlement, came in the late 1700s; then, after 1800, the Garífuna, of mixed African and Indigenous descent, arrived from St Vincent.

Belize

It took Belize many years to win its independence. Even then, it was a good few years before the country achieved true political freedom. Relations with the Spanish rulers of neighboring Guatemala were frequently tense throughout the 17th and 18th centuries, as British pirate ships used Belize’s sheltered waters as harbors from which to attack Spanish ships. As a result of the American War of Independence, Spain declared war on Britain and in 1779 a sizeable Spanish force attacked St George’s Caye, burning it and Belize Town to the ground. The settlement was rebuilt, but in 1798 the Spanish attacked again. Despite the fact that the Spanish force had far superior firepower, a decisive sea battle was fought at St George’s Caye, and the Spanish were soundly defeated.

Following this victory, the local inhabitants considered themselves part of the British Empire, although officially the colony still did not exist. In 1802, Spain was obliged to acknowledge British sovereignty over the area in the Treaty of Amiens. When Guatemala and Mexico won their independence from Spain in 1821, both laid claim to the territory of Belize. It was formally declared a British Crown Colony in 1862 and stayed that way all the way up until 1973, while the Bay Islands and Mosquito Coast were ceded to Honduras and Nicaragua in 1859 and 1860.

Gran Colombia

Panama shares a political history closer to neighboring Colombia than with the rest of Central America. After its independence from Spain on November 28, 1821, Panama became part of the Republic of Gran Colombia, which included Colombia, Venezuela, and Ecuador. The Isthmus fought for its independence with little success until 1903. After a failed French attempt at building a canal linking the Atlantic and Pacific Oceans, the Roosevelt administration proposed to Colombia that the US should build and control such a canal, offering to pay off the stockholders of the company still in control, though the Colombian government refused. A rebellion ensued and in 1903 the Hay–Bunau-Varilla Treaty was signed, giving the US permission to build a canal and then administer, fortify and defend it ‘in perpetuity’.

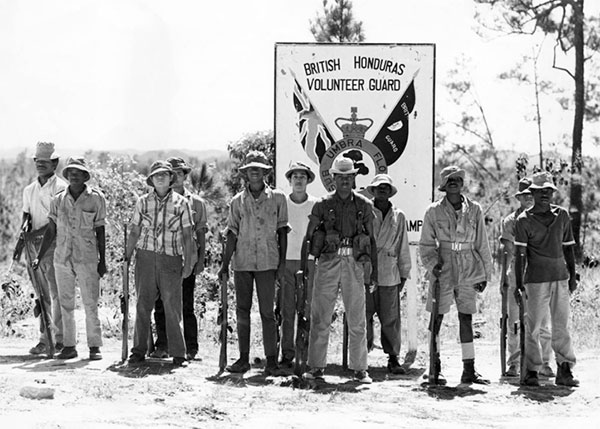

The British Honduras Volunteer Guard on parade, 1972.

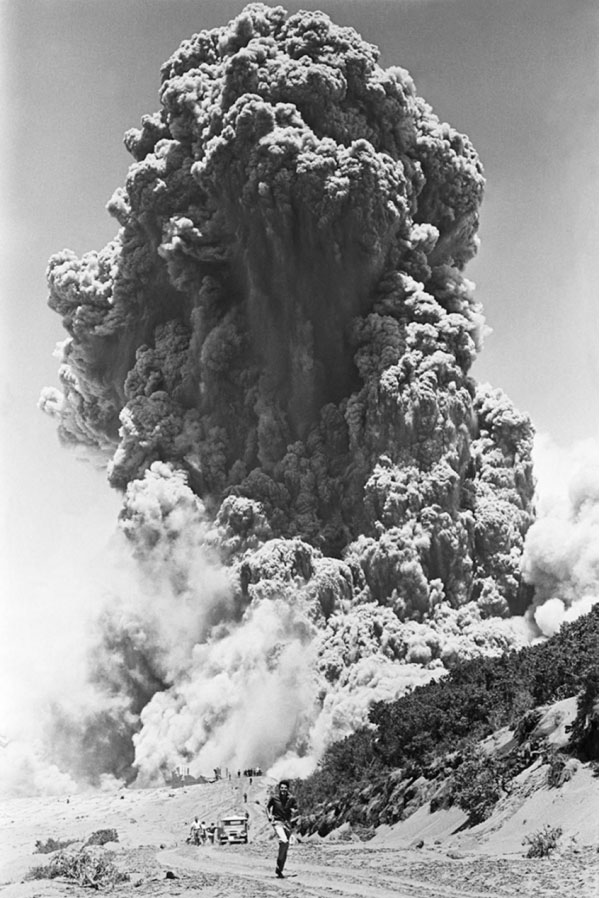

A man runs from a huge ash cloud as Costa Rica’s Mount Irabu volcano erupts, 1963.