Fact

One of the most influential early explorers of Maya sites was the Frenchman Désiré Charnay. It was he who first photographed Palenque, Uxmal, and Chichén Itzá, and these superb photographs and lithographs led the way for the first scientific archeological expeditions.

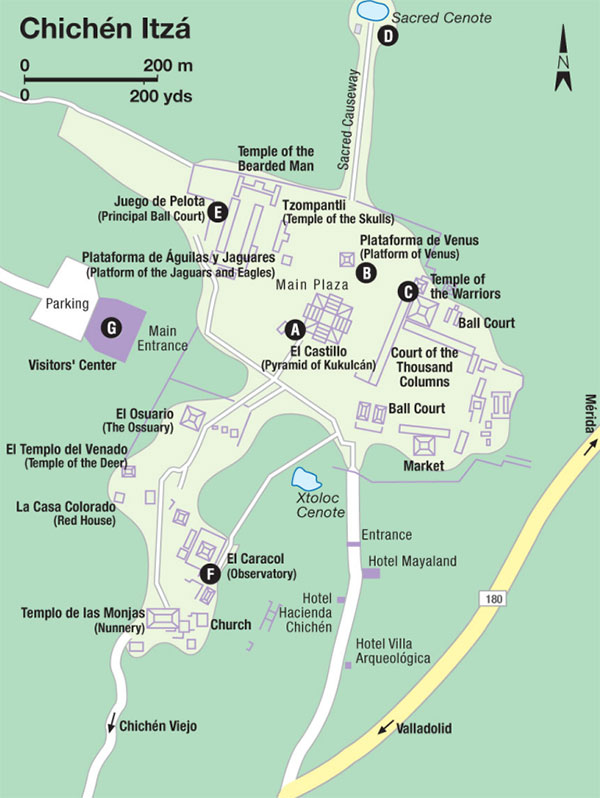

Exploring the site

On entering Chichén, the view is dominated by the 24-meter (80ft) high Pyramid of Kukulcán (El Castillo) A [map] . It represents the Maya calendar, with four 91-step staircases plus a single step at the top, adding up to 365. Eighteen terraces divide the nine levels that represent the 18 months, each 20 days long. The nine terraces symbolize the nine underground worlds. Each side has 52 panels, representing the 52-year cosmic cycle, the point at which the Mayas’ two calendars coincided and they considered that a cycle ended, only to begin anew.

El Castillo at Chichén Itzá.

Alex Havret/Apa Publications

The giant carved serpents beside the great stairway are picked out by sunlight at sunset during the spring equinox, interpreted as a time to sow the crops, just as the snake’s apparent ascension of the pyramid at the fall equinox signified harvest time. Thousands of visitors come to see this phenomenon – known as the ‘Descent (or Ascent) of Kukulcán,’ from the Maya name for the plumed serpent god Quetzalcoatl – on March 21 and September 21 every year. The illusion, which lasts more than three hours, is imitated more briefly every night during the Luz y Sonido (Light and Sound) show (Nov–Mar 7pm, Apr–Oct 8pm).

Centers of sacrifice at Chichén were the three small platforms in the great plaza to the north of the main pyramid, the Plataforma de Venus B [map] (with stairways at each side guarded by feathered serpents), the Plataforma de Águilas y Jaguares (with relief carvings of eagles and jaguars holding human hearts), and the Tzompantli, from which human heads were hung. Around it are carved grinning stone skulls in horizontal rows, on all four sides.

The east side of the plaza is filled by the Temple of the Warriors C [map] , another of the most imposing buildings at Chichén. This is another structure that you are no longer allowed to climb, to see the most famous of all the Chac-Mool sculptures at Chichén Itzá. The temple takes its name from the rows of columns at its front, carved with over 200 separate images of warriors, priests, and other figures of Chichén, each one different, almost like a ‘picture gallery’ of the city. The Warriors’ columns form a corner with the plainer pillars of the huge quadrangle called the Court of the Thousand Columns, which probably served as a market and center for public business in Chichén Itzá. A sacbé-style path to the left of the Warriors temple leads through woods to the Sacred Cenote D [map] , 60 meters (197ft) in diameter and 35 meters (115ft) deep.

Chichén Itzá’s El Osuario.

Alex Havret/Apa Publications

The enormous Juego de Pelota E [map] (96 meters/315ft long, 30 meters/98ft wide) or ball court of Chichén Itzá, completed in the year 864, is the largest ancient ball court in Mesoamerica, and on a vastly different scale from the courts usually found in Maya cities. On either side it has stone rings high on the walls, and it seems likely players had to get the solid latex ball through them to score.

There are several other structures around the site, particularly to the south of the great plaza. El Osuario, a 10-meter (33ft) tall pyramid that seems almost a ‘model’ for the later Castillo, contains an opulent tomb, the origin of its alternative name ‘The High Priest’s Grave’; La Casa Colorada, the Red House, was named for the red paint on its doorway mural. El Caracol F [map] , the fascinating observatory of Chichén Itzá, is a domed, circular tower shaped like a snail (hence its name), with roof slits through which astronomical observations could be made with remarkable precision. Farther south again, the complex the Spaniards called Las Monjas (the Nunnery) is purely Maya in style, with fantastically elaborate carved friezes, made-up stone Chac masks and mythological bacabs.

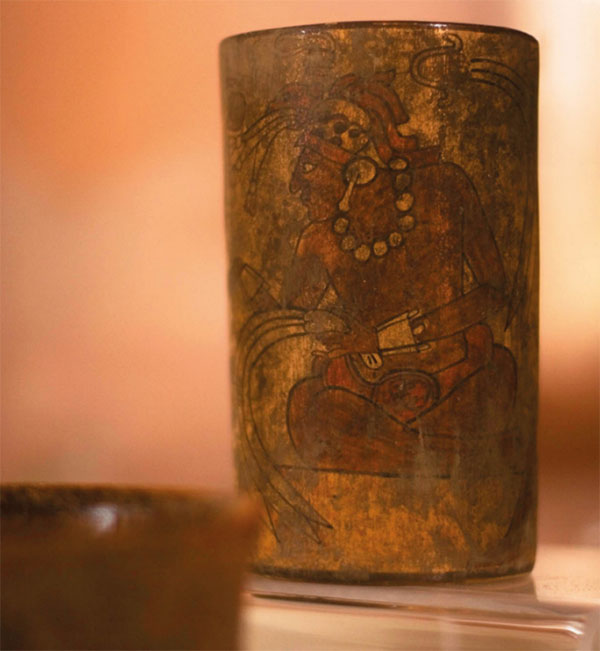

Painted ceramic on display at Museo de San Roque in Valladolid.

Alex Havret/Apa Publications

At the entrance to the ruins (daily 8am–5pm) is a large Visitors’ Center G [map] , with stores, restaurants, and a museum. Chichén Itzá is inundated with tourist buses every day of the year, but regular buses from Mérida and Valladolid also pass the site or stop in the nearby village of Piste, on the highway 1.5km (2 miles) before the site, about US$4 by taxi.

Fact

The Spanish Conquest was followed by a campaign of religious conversion. In the Yucatán, the Franciscans used Maya labor to build severely simple monasteries. Immense and majestic, with few carvings or moldings to distract the eye, they conformed to Franciscan principles of asceticism. Big timbers were scarce, but there was a plentiful supply of stone. Often, the friars reused the ‘pagan’ temple-platforms and Maya stonework.

Valladolid

Valladolid 4 [map] (population 56,000), some 40km (25 miles) east of Chichén Itzá, was once a Maya center called Zaci, but was taken over by the Spanish in 1545. Its attractively calm feel today belies its dramatic history, as Valladolid was the scene of a historic massacre of most of its white citizens during the War of the Castes, the great Maya uprising that began nearby in 1847.

The city’s colonial atmosphere is maintained by its well-preserved churches and mansions. The convent-church of San Bernardino Sisal is one of the oldest churches in the Yucatán (1552), and sits at the end of a row of colonial houses leading from the center, Calle 41-A or the Calzada de los Frailes (Street of the Friars). The Museo San Roque (daily 9am–9pm), just east of the plaza on Calle 41, has an engaging display of local relics. Valladolid still has its town cenote, Cenote Zaci (daily 9am–5pm) at the intersection of calles 36 and 39, which is fine for a refreshing dip, though its waters are a little murky. Nearby, however, there is one of the great must-sees of the Yucatán, Cenote Dzitnup, 7km (4.5 miles) west and well signposted off the highway.