Legendary ferocity

The Spanish conquest of the Maya in Guatemala was entrusted to Pedro de Alvarado. He achieved it with a ferocity that became legendary. In 1523, he and some 800 men defeated the main army of the K’iche’ and slew their leader, Tecún Umán. Alvarado then advanced on the K’iche’ capital, K’umarkaaj, and burned it down. He was equally ruthless with the Kaqchikel, and set about conquering the many mountain tribes. In 1527, Alvarado founded the first Spanish capital of Guatemala at Santiago de los Caballeros, close to the modern-day city of Antigua.

Pedro de Alvarado.

Dagli Orti/REX/Shutterstock

Resistance to Alvarado’s rule continued through the 1530s, especially in the highlands of Verapaz, where in the end it was Christian missionaries led by Fray Bartolomé de las Casas who managed to get the Maya to accept Christianity and Spanish rule. By the time of Alvarado’s death in 1541, almost the entire Maya population of Guatemala was under Spanish control. As in Mexico, however, this did not mean a complete end to resistance, and it was more than a century and a half later, in 1697, that the last descendants of the independent Maya kingdoms, who lived in Tayasal, an island on Lake Petén Itzá in northern Guatemala, were finally subdued.

Pestilence and slavery

The Spanish expeditions to Central America had brought smallpox, influenza, and plague to the area, and tens of thousands of Indigenous people died. Survivors of the epidemics faced another danger: enslavement. Indigenous communities that lived in large population centers, and were vulnerable to such attacks, were captured, branded with hot irons, and shipped off to Panamá and Peru to be sold as slaves.

During this period, the conquistadores who arrived in Central America were free to exploit the Indigenous population in virtually any way they wished. The Spanish policy of requerimiento, which went into effect in 1510, permitted settlers to wage war on those who refused to be baptized, a convenient justification for killing Indigenous groups and plundering their gold.

Later, encomienda, a royal grant from the Crown, gave settlers in Central America the right to force Indigenous peoples to labor without compensation – or to demand goods as tribute. It was, in effect, slavery. The Indigenous people were relocated to live on the land where they worked, and were considered the property of the grant holder. Without the system of encomienda, the conquistadores could not realize their aspirations of becoming landed aristocracy. All of the rights and assumed privileges of title had no real value without Indigenous peoples to work the land.

Many did not adapt well to slavery and fiercely resisted its imposition. Many fought and died avoiding enslavement, and many others fled to the mountains where they could not be followed. Finally, the practice of encomienda was abolished well before large numbers of Spanish settlers started arrived in the region.

Bartolomé de las Casas was to chronicle the methods of Spanish colonization in Latin America in his History of the Indies. He later became bishop of Chiapas, in Mexico.

Cruelty of the Spanish encomienda system on a plantation.

Alamy

Life under Spanish rule

By the mid-16th century, the original Spanish conquistadors had died, and Spanish rule was directed more impersonally from Spain and from the capital of the viceroyalty in Mexico City. The Yucatán and Guatemala (from where Honduras and Chiapas were governed) were far from these centers, and this distance on the one hand led to greater abuses, but on the other protected the Maya way of life, as it was never entirely dominated by the newcomers.

Among the first measures taken by the Spanish administration was the concentration of the native population in villages and towns, known as reducciones. Each of these was laid out in the Spanish style, with a central square where the Catholic church and the town hall or ayuntamiento were located. The local population was brought into these new villages for several reasons. It was easier for the Spaniards to control them, and to make sure they paid their taxes. They were on hand for the communal work demanded of them, while at the same time it facilitated the missionaries’ work of evangelization. In this way, the Maya were forced to become part of Spanish colonial society – which, in a very racist way, always regarded them as the lowest element in that society.

As the Spaniards developed agriculture and their estates or haciendas extended throughout the region, they also forced the Maya to work there – and in Guatemala, for example, began the wholesale transfer of laborers from the highlands down to the plantations on the Pacific coast. Spain’s Central American colonies gradually developed, with administrative centers springing up in Panama, Nicaragua, and Guatemala, while the name ‘Costa Rica’ was used for the first time in 1539, to distinguish the territory between Panama and Nicaragua.

Skillful adaptation

Although some Maya were given posts of minor authority in the new Spanish villages, there was little chance of them wielding any real power. Instead, they continued their traditional practices and communal organization in parallel with the Spanish system.

Authority in the more remote villages continued to be held by the principales or village elders. Communal efforts were organized among Maya cofradías or brotherhoods, who used their role as keepers of the local saints to run self-help schemes, joint work on the milpas (maize fields), or even land transfers among villagers. Together with this, the colonial Maya were skillful at adapting the Christian religion to their own beliefs, continuing to worship the old gods in the guise of the Christian pantheon.

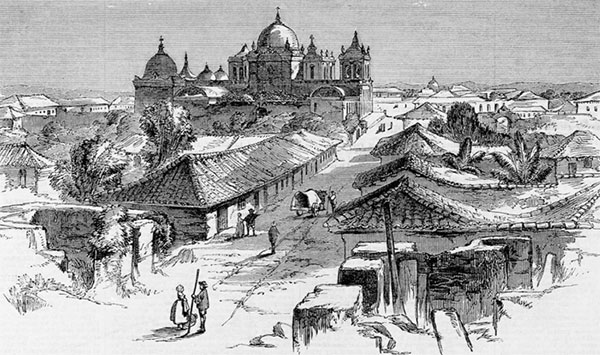

The cathedral and city of León, Nicaragua.

Bourbon influence

For more than two centuries after the Spanish Conquest, these efforts and the isolation of much of the Maya world from the centers of Spanish interest helped to protect the Maya from the worst ravages found elsewhere in the empire. The Maya’s position worsened considerably during the second half of the 18th century, however, when the Bourbon monarchy in Spain attempted to regain effective control of its rebellious colonies. The provinces were subdivided and reorganized into intendencias and partidos, and Indigenous officials were removed from office and replaced by Spaniards or criollos.