Behind much of New Zealand’s art and literature lies a degree of tension between the landscape and the people who inhabit it.

Many New Zealanders have always had something of an ambivalent attitude towards the arts. Grants to artists and writers by the state funding agency once regularly aroused derision, as if wastrels and idlers were getting money for nothing. Today philistinism is never far from the surface. But in spite of this – or perhaps precisely because of it – a robust Indigenous culture has flourished. The very isolation of artists has forced them to forge their own way, without too much reliance on overseas models or local encouragement.

A potter hand throws a clay bowl in his studio in Māpua.

Peter James Quinn/Apa Publications

The practical do-it-yourself tradition of New Zealanders in other fields – notably farming and home renovation – shows through in the work of artists as diverse as the inventive Michael Parekowhai, who represented New Zealand at the 2011 Venice Biennale, and the masterful late Ralph Hotere, whose paintings frequently incorporated materials like corrugated iron and old timber. More contemporary issues like business innovation and information technologies are explored by the high-profile sculptor and installation artist Simon Denny, who represented the country at the 2015 Venice Biennale. His exhibition, Secret Power addressed concerns relating to the ownership of knowledge, and the role of New Zealand in an intelligence alliance between Australia, Canada, the United Kingdom and the United States (the Five Eyes). In 2017, Lisa Reihana represented New Zealand at the Venice Biennale with her panoramic video Emissaries.

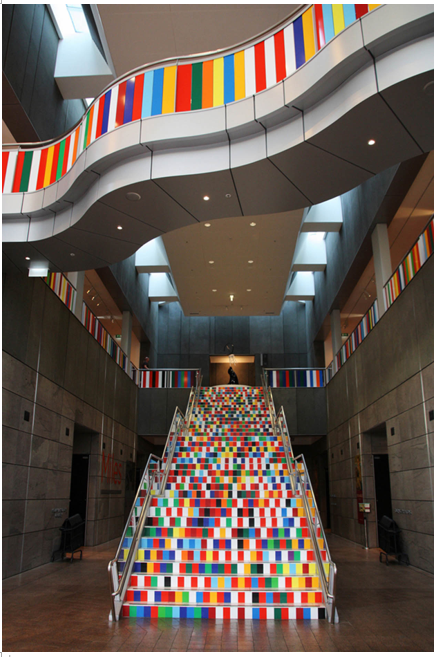

It remains a scandal that there is no national art gallery in New Zealand. The remains of what used to be one have been squeezed into an upstairs space at Te Papa, and although the museum itself is a must, don’t expect to find a truly representative display of New Zealand art here. Instead you should trawl the fine range of city and provincial galleries – notably the superb Christchurch Art Gallery (for more information, click here). The long wavy line of its glass-and-metal exterior hints at the shape of the koru, a stylised fern frond that also decorates the tails of Air New Zealand planes and symbolises growth and harmony.

Solace in the Wind’ sculpture by Max Patte overlooking Wellington Harbour.

Shutterstock

FINE ART

One of the first artists to be exhibited at the new Christchurch Art Gallery when it opened in 2003 was W.A. (Bill) Sutton, the long-lived local painter (1917–2002) whose spare, semi-abstract landscapes seem to symbolise the artist’s relationship with the land – often perceived in New Zealand art as empty, brooding, even hostile to humans.

The hugely popular realist landscapes of Grahame Sydney, though softer in style, catch some of this mood. Sydney’s work has been likened, with good reason, to that of the late American painter Andrew Wyeth. The godfather of New Zealand art, as it were, is Colin McCahon (1919–87), whose work moved beyond simple landscapes with religious connotations to vast, dark, mystical incantations whose brooding power lay as much in the prayers inscribed upon them as in their massive cubist forms.

But contemporary New Zealand art is not all gloom and doom. McCahon’s less tormented successors have been more inclined towards playfulness and postmodern irony in their work, particularly artists like Joanna Braithwaite, Kushana Bush, Shane Cotton, Dick Frizzell, the late Don Driver, Richard Killeen, Peter Robinson and the quirky Bill Hammond, of whose surrealist paintings it has been said: ‘Everything about them is odd.’

Neil Dawson’s much-loved ‘Ferns’ was removed from Civic Square, Wellington in 2015 amid safety concerns.

Shutterstock

SCULPTURE AND POTTERY

Sculpture has always laboured to find its feet in New Zealand. The size of the country and a perception that money spent on art is not money well spent has meant that public commissions are rare and grudging. Sculptors tend to work on a small scale, but there are two who merit particular attention. Terry Stringer’s work often playfully exploits the tension between the firmness of bronze, one of his favourite media, and the softness of his subject matter. Something of a traditionalist, though often with a postmodern edge, Stringer is also an accomplished portrait painter.

The South Island city of Nelson is renowned for its wealth of talented artisans, and the region possesses more working artists per capita than anywhere else in New Zealand.

Experimentation with light is regarded as the province of the painter, but Neil Dawson creates sculptures in which the shadows cast by the work can be equally as important as the shapes he has moulded out of such favoured materials as aluminium and steel. His dramatic Ferns usually hover above the Civic Square in Wellington (at the time of writing the sculpture had been removed for repair), and his major overseas commissions include Globe at the Pompidou Centre in Paris, and Canopy for the Queensland Art Gallery in Brisbane.

Francis Upritchard and Rohan Wealleans, both born in the late 1970s, are some of the new hot names in the world of sculpture who have gained international recognition.

It’s not entirely clear why pottery has long been such a popular creative endeavour in New Zealand. There are two representative currents. The first is the rough-hewn, hands-on, earth-connecting style. One iconic name in this field is Barry Brickell at Coromandel’s Driving Creek Railway and Potteries (for more information, click here). The other strand is a more ‘fine art’ approach represented by John Parker, who has worked for years producing pottery solely in white, in which an elegant severity of form and line is a major concern.

Outside the mainstream of New Zealand art – and outside the country for much of his life – is Len Lye (1901–80). Lye worked in numerous media but is mainly remembered as a kinetic sculptor and pioneer of direct film, in which he scratched and otherwise worked directly on film to create entrancing abstract images. These were set to music in a way that has resulted in them being described as proto-music videos. The Govett-Brewster Art Gallery in New Plymouth (for more information, click here) holds the Len Lye collection and archive, and regularly exhibits his work. His arresting sculpture Wind Wand has been installed on the New Plymouth foreshore.

LITERATURE

The first New Zealand writer to attract significant attention outside her own country was Katherine Mansfield, whose delicate short stories have – despite her own gloomy prediction – survived numerous changes of fashion and can be read with as much pleasure today as when they were written, mostly in the 15 years or so before her death in 1923 at the age of 34. New Zealand in the early 20th century was claustrophobic for the young writer, and in 1908 Mansfield left her country, with some eagerness, in pursuit of a career – first in London and later in Switzerland and the south of France. She never returned.

Not until 1985 was another New Zealander as widely read, when the Booker Prize was awarded to Keri Hulme for The Bone People. The book has been translated into some 40 languages and has sold millions of copies worldwide. It’s Hulme’s only novel. A difference between the two writers that summarises the development of New Zealand literature is that Mansfield’s work, with its lightness of touch, was only marginally concerned with New Zealand issues, while Hulme’s monumental work was almost aggressively focused on issues of national identity and biculturalism alongside more universal themes.

Christchurch Art Gallery interior.

Shutterstock